Phillip Jacob Runser (30 Jun 1845 - 22 Mar 1921), a maternal second great-grandfather, was born in Hégenheim, in the Alsace region of France--just a landslide away from the Swiss border--where Runsers can still be found. He was the seventh of eight children, and was named after his father.

(I would be fascinated to know how Phillip and Clara, as she was known, met, as her family worked primarily as sailors and such along the Great Lakes, while the Runsers were farmers in central Wisconsin. I do not know where she was living in 1870, as I cannot locate her on the U S Census for that year. The John Borden Wilbor family, with whom she was living in 1860, was still in Erie, Ohio, but Clara was no longer living there. Did she go to Wisconsin? If so, why? I have no indication that Phillip or any of the relevant Runsers visited Ohio.)

Anyway. Black River Falls, home to numerous Runsers and their relations, is the subject of both a book (by Michael Lesy, 1973) and documentary film (by James March, 2000) entitled Wisconsin Death Trip. Both works feature extremely disturbing stories, and photographs taken in Black River Falls during the late 1800s by Charles Van Schaick. The film is highly recommended as a look at what our ancestors endured. It is no wonder that within a few years the newly-married Runsers moved to the Dakota Territory, settling in Redfield, Spink County sometime around its formation in 1879.

|

| Black River Falls a few years after the Runsers left. Photo by Charles Van Schaick, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. |

The Runsers acquired more acreage, and with it, apparently, some financial success. The first school in Spink County was built on one acre of land on the NE corner of NW 1/4 Section 25, Twp.117, Range 64, donated by P J Runser, Sr. Perhaps this altruistic gesture served as the catalyst for the love of learning that runs through our family, and led to many of P J Runser's descendants becoming educators. Several of his grandchildren attended the school, which stood in the same location for over fifty years. It was later moved (a new school built in its place), and used as a meeting hall for the Farmer's Union, then finally torn down in 1975.

In 1888, Phillip co-founded a company, the Redfield Elevator Company, for "Buying, selling and shipping grain and farm products."

|

| Notice of incorporation of the Redfield Elevator Company, from the Bismarck [North Dakota] Daily Tribune, 9 Dec 1888. |

His entire adult life was spent in farming, so perhaps it is not surprising that a few years later Phillip invented a gizmo to be used on farm equipment. His "Speed-Changing Device and Indicator" was patented on 8 Feb 1898 as U S Patent number 598,817.

|

| Page one of a three-page explanation of the device. |

|

| Note the engraving of PJR's signature in the lower right. |

In a previous post, I had quoted from a distant relation who bemoaned the detailed pedigrees of livestock, in lieu of focusing on human lineage. At the time, I imagined he was hyperbolizing, but researching Phillip, I discovered that these animal genealogies actually exist. In my second great-grandfather's case, I was able to find his name in several hefty tomes with titles like The American Oxford Down Record, Vol 5 (1892, page 391) as the owner of what were apparently several prized animals, including American Oxford and Vermont Merino sheep, and American Poland-China hogs. From 1901:

|

| Some pig. |

Like his father, Phillip also had eight children, including a son who became the third Philip Jacob Runser (26 Oct 1884 - 10 Nov 1984). Strictly speaking, he was not the third, as his grandfather went by Phillipe, and his father by Phillip, seemingly losing a letter with each generation; however, we will not let orthography get in the way of sentiment. At any rate, as of 2010, there was still a Philip (or perhaps, by this point, just Phil) J Runser--the sixth--living in Foxboro, Wisconsin.

A few years later, Phillip and Clara, after living for a short time in Minnesota, finally returned to Wisconsin, this time to Douglas County. As late as 1910, aged sixty-five, Phillip Jacob Runser's occupation on the U S Federal Census was still listed as "Farmer." He died in 1921, just a year after his wife; his children Kitty, Joseph, and Philip and their families living on adjoining farms.

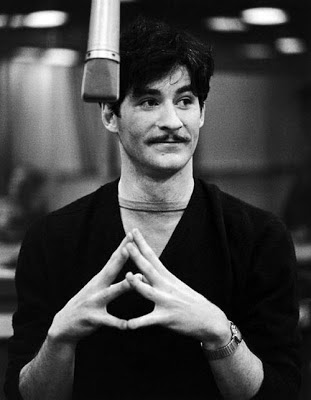

|

| Summit Cemetery; Foxboro, Douglas County, Wisconsin. |